Hanover Bald Eagle Blog # 6 - 2020

In partnership with Pennsylvania Game Commission and Comcast Business .

Right now, as Liberty and Freedom are sitting on their soon-to-be-hatchling, there are thousands of other bald eagles soaring their way northward who have yet to begin nesting. The magnitude of bald eagle migration is documented annually by hawk watch sites across North America, through the dedication of volunteers and paid counters. These efforts are intended to reveal long-term population trends and bolster our understanding of this magnificent species.

Watch sites are strategically positioned on ridge tops where migrant raptors utilize updrafts and thermals (rising spirals of warm air) to catch lift, therefore saving energy on their long journeys northward. In just the last two weeks, Hawk Ridge Bird Observatory has counted 1,219 migrating bald eagles at their watch site near Duluth, Minnesota!

That’s a lot of eagles.

If the Hanover eagles are more than a month into incubation, how is it possible that other bald eagles can afford to be so far behind? The answer lies in the diversity of migration patterns that exist across populations. For many eagles, seasonal movement is influenced strongly by the availability of fish.

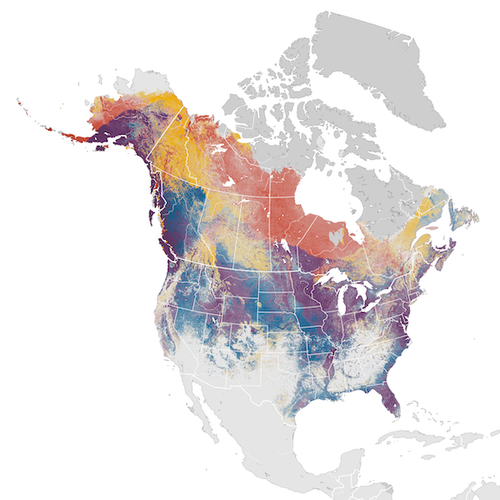

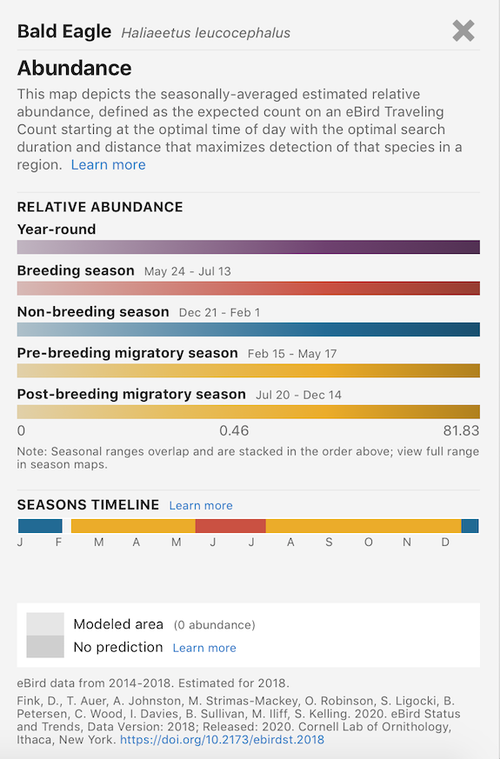

This map shows the relative abundance of Bald Eagles at different points within their annual cycle. For example, the dark purple sections such as Florida and Alaska indicate that high numbers of bald eagles are seen there year-round. In Pennsylvania, more eagles are counted year-round in the western part of the state than eastern. These estimates are based on eBird data, providing a strong example of how citizen science benefits our understanding of the natural world. Visual courtesy of eBird and Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

To further understand these variable movement strategies, let’s take a look at two nesting grounds, one in a southern part of the continent and one in the north. Many bald eagles nesting in Florida actually travel north in the summertime because the surfaces of lakes and other bodies of water heat up to the point where fish relocate lower down in the water column, becoming inaccessible. Even though bald eagles are ambitious (sometimes rowing themselves to shore rather than give up a fish), they are not diving birds. Floridan eagles that move north to fish in the summertime return to Florida in the winter and breed when their primary food source is easier to catch. This results in a migration pattern that does not match any other bald eagle population that we know of in North America.

Eagle rowing to shore, photo courtesy of Daven Hafey.

Bald eagles nesting near Lake Superior or Lake Winnipeg migrate through the upper Midwest, crossing through the aforementioned watch site (Hawk Ridge) in March. These breeding adults are timing their chick-rearing with plenty of open water. Just as many songbirds time their return migrations with insect hatches on their breeding grounds to ensure their chicks will have enough to eat, bald eagles seem to be aware that if they try to nest in a northern region too early, fish will be sealed below ice. Eagles are attuned to these timing nuances within the landscape, and even immature eagles demonstrate this by arriving later than the breeding adults. Since they are not yet raising young, they don’t need to re-establish territories or modify a nest. By arriving when the ice has already melted, they have immediate access to a hunting ground.

Salmon at the end of their spawning. Courtesy of Daven Hafey.

Another example of carefully timed eagle movement occurs in the Pacific Northwest where populations are well attuned to the fluctuations of salmon spawning. Many migrate north to southeastern Alaska to meet salmon at the end of their journey.

And then there are bald eagles who stay in the same place year-round because they have no reason to leave. Migration is energetically taxing and often dangerous. In areas where the foraging is good, the climate is good, and the competition is manageable, it may pay off to just stick around.

You may be wondering how anyone can possible pinpoint the location of an individual bird remotely, let alone identify its migration route. In addition to passage documentation at hawk watch sites, satellite transmitters have become widely used tools for revealing movement patterns. Researchers attach devices onto the backs or tail feathers of birds, ensuring they are light and flexible enough so as not to impede flight and/or safety of the bird (for example, transmitters must be less than 3% of the bird’s body mass). Through the cellular network or satellite system, detailed information about a bald eagle’s whereabouts is collected by the transmitters and then sent to a researcher, sometimes right to their email! These technological innovations are unveiling crucial information about the journeys of migratory birds, not only strengthening our awe, but also allowing us to better protect habitats along their migratory pathways.

Transmitter deployment, photo courtesy of Myles Lamont.

How incredible to think that while we watch Liberty and Freedom at the end of their incubation stage, there are thousands of eagles that haven’t even reached their nest. The range of movement strategies that exist within this one species is a true confirmation that no two bald eagle populations are alike, and furthermore, that eagles have an impressive tool belt with which to adjust their habits. We would do well to take a lesson from the eagles, and remain adaptable.

EAGLE UPDATE

The Hanover eaglet is due any minute now! Even though we haven’t yet seen signs of emergence, it can take several days for the little one to nudge its way into the world. The process has likely already begun, and the chick may be using its egg tooth to scratch towards the surface this very moment. Keep your eyes peeled!

QUIZ YOURSELF!

Are bald eagles altricial or precocial?

SOURCES

Bald Eagle Abundance Map. (2018). Retrieved from: https://ebird.org/science/status-and-trends/baleag/abundance-map

Bildstein, Keith. (2017). Raptors, the Curious Nature of Diurnal Birds of Prey. Cornell University Press.\

Mandernack, B., Solensky, M., Martell, M., Schmitz, R. (2012). Satellite Tracking of Bald Eagles in the Upper Midwest. Journal of Raptor Research, 46(3): 258-273. Retrieved March 15th, 2020, from https://doi.org/10.3356/JRR-10-77.1

Mojica, E., Meyers, J., Millsap, B., & Haley, K. (2008). Migration of Florida Sub-Adult Bald Eagles. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology,120(2), 304-310. Retrieved March 15, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/20456147

Written by Zoey Greenburg

RETURN TO HANOVER BALD EAGLE BLOGS

WATCH THE HANOVER BALD EAGLE LIVE CAMS

For over 20 years, HDOnTap has provided live streaming solutions to resorts, amusement parks, wildlife refuges and more. In addition to maintaining a network of over 400 live webcams, HDOnTap specializes in design and installation of remote, off-grid and otherwise challenging live streaming solutions. Contact press@hdontap.com for all media needs, including images and recordings.