Hanover Bald Eagle Blog # 23

In partnership with Pennsylvania Game Commission and Comcast Business .

The appearance of the Hanover eaglets has changed rapidly over the course of the last week, most notably in the transformation of their feathers. One day they look like a giant cotton ball, the next there are traces of brown popping up in seemingly random patches along the bird’s bodies, giving them a humorously disheveled look. As with many patterns in the natural world, however, there is a method to the madness.

Feathers serve several important functions throughout the life of a bird, namely by facilitating insulation and protection against outside elements, providing a pallet for color, and by making the phenomenon of flight possible. For feathers to fulfill each of these roles, they must develop at the right time, and in the right way.

The Hanover eaglets are smack dab in the middle of this crucial process, yet contrary to what we might expect, their feathers are not developing uniformly across their bodies. Feathers are distributed along tracks, called pterylae, and if you look closely at the nestlings you can see evidence of this pattern in their current attire.

The arrangement of these tracks differs among groups of birds depending on factors such as flight behavior and climate. Feather tracks are likely beneficial by reducing the weight or “baggage” that a bird lugs around during flight. Growing feathers in restricted yet strategic areas allows a bird to concentrate their muscle development and feather load to places where the two are most needed, rather than across their entire body which would add more overall weight, making them less adapted to flight. Furthermore, by leaving areas of bare skin in between feather tracks, birds maintain the option of simply raising their feathers (called piloerection) to cool off when necessary.

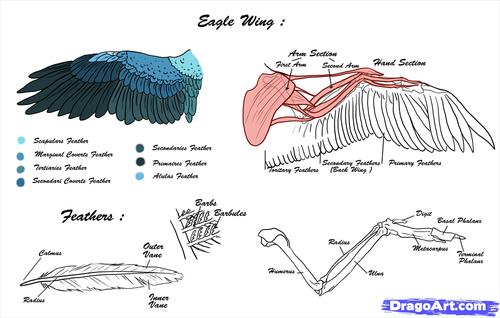

There are several types of feathers that all birds need. Contour feathers are what we see when admiring a bird from the outside. In essence, they are the external layer. Because they function as the first line of defense to the world, they are quite literally zipped together through a complex structure of interlocking pieces of feather called barbules. The largest of the contour feathers are those that make up the wing, called remiges, which are further divided into primary and secondary feathers. The primaries are the furthest wing feathers from the bird’s body. The secondaries are the next group in, closest to the bird’s body. Then there are coverts, which are rows of feathers that border the flight feathers and tailfeathers. The coverts are a critical category of feathers as they provide color, pattern, insulation, and most importantly, they reduce friction by streamlining the shape of the bird’s wing.

Between contours, primaries, secondaries, coverts, and tailfeathers (called rectrices), most of the bird’s body is covered. There are, of course, many specialized feathers such as the ornamental peacock feathers, or those of birds of paradise, used in courtship displays to attract the female. Owls possess fringe on the edges of their flight feathers that muffle their sound as they prowl through the night looking to surprise unexpecting rodents. Some birds that specialize in catching insects such as nighthawks have small face-feathers called rictal bristles, which are thought to function like whiskers or eyelashes, improving sensitivity and keeping debris out of the bird’s eye as it swoops through the air snatching winged invertebrates.

Raptors and many seabirds possess a layer of feathers called body down, for added insulation. This is different than the light-colored natal down, which is what gave the Hanover eaglets their cotton ball impression. This stage of baby fluff, which arises from the same follicles that will later produce contour feathers, only lasts about 10 days, after which a similar but more sophisticated layer of body down begins to form that will serve the eagles well their whole life. Body down traps air securely in a tangled net of chaotic feather barbules and will allow the eagles to withstand the cold. After two weeks of age, eaglets are able to thermoregulate on their own with this new layer, which, along with the fact that the eaglets are too big, and the weather has warmed up, explains why we no longer see Liberty or Freedom tucking the young underneath their breasts to keep them warm.

Eloquently stated in the Handbook of Bird Biology, the “gradual replacement of natal downs with darker body downs, and eventually juvenal contour feathers makes these [eagle] nestlings look like clean, white snowmen, growing increasingly dirty and angular in the winter’s afternoon sun.” I think we can all agree this description fits the Hanover eaglets well.

Bald Eagles do not reach full adult plumage with a white head and tail until five years of age, hence the reason why young Bald Eagles are commonly mistaken for their all- brown cousin, the Golden Eagle. The dark brown body feathers that characterize young Bald Eagles first develop along feather tracks on the head and the back, with the stomach feathers arriving last. Wing and tail feathers develop throughout the nestling phase and won’t reach full length until the young are ready to take their first flight. Juvenile Bald Eagles have slightly longer flight feathers than adults, giving them a larger appearance. These long feathers will be replaced by “normal” sized ones after their first molt.

RESOURCES

The Center for Conservation Biology. (2019). Bald Eagle Chick Development. Retrieved from

https://ccbbirds.org/2011/04/30/bald-eagle-chick-development/

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (2004). Handbook of Bird Biology. Princeton: NJ: Princeton University Press.\

THANK YOU HAWK MOUNTAIN FOR THIS WEEK'S BLOG ENTRY!

RETURN TO HANOVER BALD EAGLE BLOGS

WATCH THE HANOVER BALD EAGLE LIVE CAMS

For over 20 years, HDOnTap has provided live streaming solutions to resorts, amusement parks, wildlife refuges and more. In addition to maintaining a network of over 400 live webcams, HDOnTap specializes in design and installation of remote, off-grid and otherwise challenging live streaming solutions. Contact press@hdontap.com for all media needs, including images and recordings.