Hanover Bald Eagle Blog # 5 - 2022

In partnership with Pennsylvania Game Commission and Comcast Business .

Word on the street is that the Hanover female revealed some loosened feathers on her breast this week, which could mean an egg is on the way! Breeding bald eagles develop brood patches, which are bare patches of skin on the breast that help them keep the eggs warm during incubation. Both parents incubate, called biparental incubation, and both develop brood patches. Specific hormones (prolactin and estrogen/testosterone) trigger feather loss and increased vascularization in the breast area of both parents when the time of egg laying is near. This process is part of the chain of events mentioned in Blog 3, during which the eagle’s bodies respond to both external and internal cues telling them it’s time to get ready for chick rearing. These are exciting times!

The eagles will spend more quality time in and around the nest as they prepare for the first egg’s arrival. Last year the Hanover eagles laid their first egg on February 3d and their second egg on February 5th. Their breeding schedule varies between years, but we are certainly within the laying window. The Hanover family could grow in size any day now.

The Hanover Eagles just this afternoon, Freedom comes in with fresh catch of the day, Liberty eats in the nest.

There was a time, however, when bald eagle parents were unable to breed at all. Year after year nests failed, and eagle lovers looked on in horror as the North American population dwindled. Among conservationists, the story of bald eagle recovery is the stuff of legend. There are few North American animal species that have bounced back from such a close brush with extinction. And, as is too often the case, humans were responsible for their peril as well as their resurgence.

Prior to the 1940s, bald eagles throughout North America were treated poorly. Raptors in general were widely villainized, and there were no laws preventing their slaughter. Rather, their demise was encouraged. Additionally, the rise of industry threatened the aquatic habitats eagles depended upon, and, following World War II, a deadly insecticide turned their world upside down.

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) was lauded for its swift removal of disease-carrying mosquitoes and other insects that impacted agricultural productivity and the flourishing of home gardens. Throughout the 1940s large volumes of DDT were sprayed. By the 1950s and ‘60s, concern was brewing over the potential harm caused by DDT, and in 1962, Rachel Carson solidified these concerns in the publication of her book Silent Spring. She systematically and passionately outlined the detrimental effects of DDT and other chemicals on both the environment and human health. This book was one the most influential texts in conservation history, and inspired communities across the nation to demand healthier restrictions on chemical usage. Policy makers were pressured into regulating the use of DDT. In 1972, following the development of the Environmental Protection Agency, DDT was finally banned.

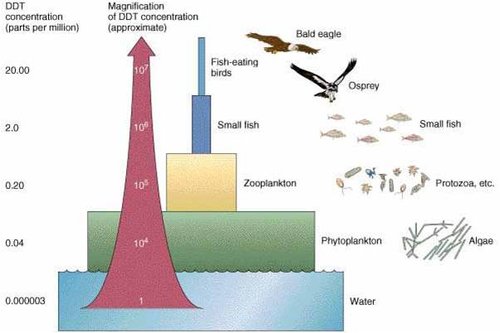

Between 1940 and 1972, however, DDT had made its way up the food chain through a process called bioamplification: Insects afflicted with DDT were consumed by fish, which were consumed by bald eagles. Bald eagles ended up with much higher levels of contamination than species further down the food chain, because, as top predators, they consumed large numbers of already-contaminated prey.

Image: Eric Wortman, Trophic Levels, Biomass Pyramids, and Bioaccumulation

DDT threatened populations of bald eagles, peregrine falcons, and many other birds by preventing individual females from producing enough calcium, which in turn weakened their eggshells. During incubation, the eggs broke. This seemingly simple hiccup in breeding biology quickly resulted in catastrophic declines. Bald eagles were given protection through the Endangered Species Act in 1967, but by then, far-reaching damage was already done.

Although DDT was banned in 1972, it continued to impact ecosystems for years to come. By 1963 there were only 417 nesting bald eagle pairs in the lower 48 states, and by 1983 there were only three remaining nests in Pennsylvania. At this time, the PA Game Commission (est. 1895) initiated a local reintroduction program, which succeeded in part because people were striving to restore bald eagle habitat. Keeping eagle chicks alive was one thing. Ensuring they had a healthy home for them to return to was another.

The bald eagle was federally removed from the Endangered Species list in 2007. However, they are still protected under the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, and the Lacey Act.

It has been a tumultuous road for our national symbol. The recovery of the bald eagle was tied to the ebb and flow of human understanding. It took a combination of events to turn the tide in favor of the eagles: Scientific data showing the species’ decline, Rachel Carson’s compelling and honest narrative, the public’s willingness to speak up on behalf of birds in need, the eventual implementation of effective policy, and the formation of reintroduction programs. Today, we are fortunate to see the results of these efforts in the beautiful unfolding of the Hanover nest, where most years, a healthy chick breaks through a healthy eggshell. Let us remember how close we came to losing this species forever, and do what we can to protect them in the future.

Note: History buffs can view a more detailed account of the bald eagle recovery timeline in North America by reading the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service’s overview. Pennsylvania’s recovery plan was outlined under the Chesapeake Bay Region Plan.

Sources

Fisher et al. (2006). Brood Patches of American Kestrels Altered by Experimental Exposure to PCBs. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, 69 1603-1612.

Pennsylvania Game Commission. (2022). Bald Eagle Reintroduction. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. https://www.pgc.pa.gov/Wildlife/WildlifeSpecies/BaldEagles/Pages/Reintroduction.aspx#:~:text=A%20group%20of%20Game%20Commission,1%2C500%20breeding%20pairs%20of%20eagles.

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. (2018, September 26). Bald & Golden Eagle Protection Act.

https://www.fws.gov/birds/policies-and-regulations/laws-legislations/bald-and-golden-eagle-protection-act.php

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2021, December 21). Lacey Act. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/planthealth/import-information/lacey-act/lacey-act#:~:text=The%20Lacey%20Act%20combats%20illegal,wildlife%2C%20fish%2C%20and%20plants.&text=%C2%A7%C2%A7%203371%2D3378)%20and,product%20that%20was%20illegally%20harvested.

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. (2020, April 16). Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

https://www.fws.gov/birds/policies-and-regulations/laws-legislations/migratory-bird-treaty-act.php

RETURN TO HANOVER BALD EAGLE BLOGS

WATCH THE HANOVER BALD EAGLE LIVE CAMS

For over 20 years, HDOnTap has provided live streaming solutions to resorts, amusement parks, wildlife refuges and more. In addition to maintaining a network of over 400 live webcams, HDOnTap specializes in design and installation of remote, off-grid and otherwise challenging live streaming solutions. Contact press@hdontap.com for all media needs, including images and recordings.