Hanover Bald Eagle Blog # 2 - 2023

In partnership with Pennsylvania Game Commission and Comcast Business .

For us nest cam viewers, it may feel as though eagle life stops when the family departs from the nest for their winter adventures. However, life continues. Now that the pair has returned to the nest, we can pause to wonder — what have they been up to since we saw them last?

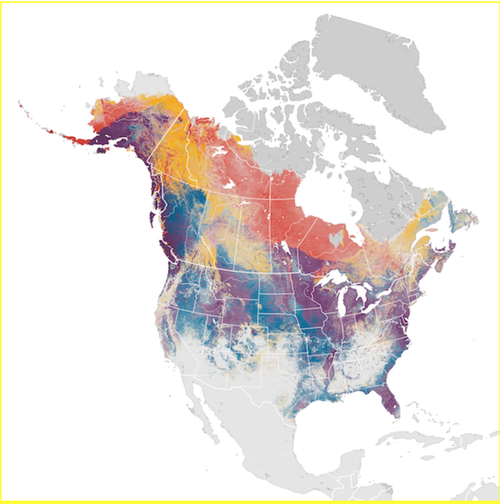

Winter activities vary between populations of bald eagles, and between individuals. Bald eagles are opportunistic, meaning they take advantage of resources wherever and whenever they can, a trait shared by many scavenging species, including turkey vultures, crows, and ravens. These species are capable of last-minute decisions, which increases their chances of thriving amidst environmental change.

Several populations of bald eagles migrate between breeding and overwintering grounds. These include pairs that breed in northern climates, where inclement weather and food scarcity are expected. Heavy snowfall can pose challenges to bald eagles, as their diet includes carcasses, especially during winter when fish are harder to come by. Snow covers carcasses up. Bald eagles are big birds, so physiologically they can survive cold temperatures better than many of their raptor cousins — but they still need protected roost sites, and they still need to eat. A food shortage will push an eagle to travel.

Roost sites offer shelter, resting perches, and the ability for individual eagles to swap information. Researchers sometimes refer to popular roost sites as “information centers” because vultures and eagles may congregate to make finding food easier. An individual can watch the comings and goings of others and then follow.

The Hanover Eagles Perch at two locations around the nest, the Lakefront Perch and the Sentinel Tree, yesterday they were seen both perched watch the clip below of this behavior:

Some bald eagles move short distances during the winter, only going as far as necessary. Others stay on their breeding grounds, close to their nest, keeping watch over their territory, nest site, and / or their mate. The Hanover eagles fall into this category, as their presence is fairly consistent year-round. This is good news — it means the pair is finding enough food and shelter close to their Hanover home.

What about the eaglets?

After leaving the nest, last year’s eaglets continued to be fed by their parents for anywhere from 4 to 11 weeks. Begging calls, which alerted the Hanover parents to the location of the fledgling, would have decreased as the youngsters began feeding themselves. This period is called the post-fledging dependence period.

At 17 to 23 weeks of age, the relationship between eaglets and parents likely began to dissipate, and eventually, the young ones officially disperse. Dispersal is defined in the Encyclopedia of Ecology as the “process by which individuals move from the immediate environment of their parents to establish in an area more or less distant from them.” For bald eagles, these distances vary — males tend to disperse sooner than females, yet remain closer to their place of birth. However, few immature eagles end up settling close to where they came from. These dispersal movements are difficult to study without using satellite tracking devices, and even then, researchers are challenged in proving why an individual chose to take the path it did. Food is often part of the equation.

Juvenile bald eagles learn how to feed themselves on the fly (literally and metaphorically) by taking advantage of landfills, butcher scraps, and literally anything edible they can find until they develop adequate fishing techniques (eagles have even been observed fighting over bread in lean years). Bald eagles are also surprisingly efficient runners, and immatures utilize a combination of clumsy flight, ground maneuvering, and jumping during their initial foraging forays.

The first year of an eagle’s life is the most perilous, with a mortality rate of over 50%, but after that their chance of survival increases dramatically. The end of summer and fall seasons were likely tough for the Hanover eaglets, but with such experienced and diligent parents, they could be pushing their way to the front of a juicy carcass as we speak!

Sources

Buehler, D. A. (2020). Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.baleag.01

Ellis, David H. (1979). Development of Behavior in the Golden Eagle. Wildlife Monographs, 70, 394-486.

Fath, Brian (2018). Encyclopedia of Ecology. 2nd Edition. Elsevier.

Gerrard, Jon M. and Bortolotti, Gary R. (1988). The Bald Eagle, Haunts and Habits of a Wilderness Monarch. Smithsonian Institution.

O’Toole, Laura, T. et al. (1999). Postfledging Behavior of Golden Eagles. The Wilson Bulletin, 111(4), 472-477.

Raptor Ecology Specialist - Zoey Greenberg

RETURN TO HANOVER BALD EAGLE BLOGS

WATCH THE HANOVER BALD EAGLE LIVE CAMS

For over 20 years, HDOnTap has provided live streaming solutions to resorts, amusement parks, wildlife refuges and more. In addition to maintaining a network of over 400 live webcams, HDOnTap specializes in design and installation of remote, off-grid and otherwise challenging live streaming solutions. Contact press@hdontap.com for all media needs, including images and recordings.