Hanover Bald Eagle blog # 17

Feb. 29, 2024

In partnership with Comcast Business and Pennsylvania Game Commission .

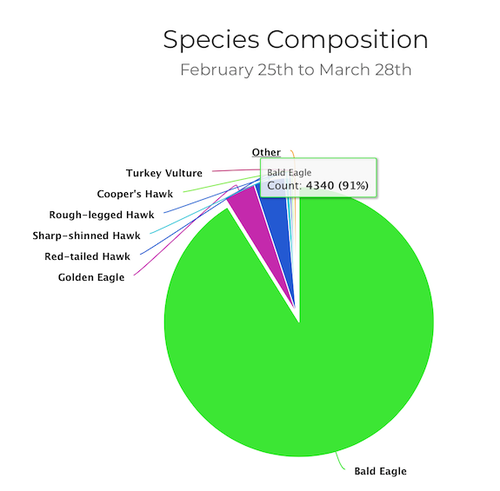

Right now, while Liberty and Freedom are sitting on a nest, there are thousands of bald eagles engaged in flight, returning to breeding grounds to begin the process themselves. Hawk watch sites across North America are reporting sightings, and on March 21st Hawk Ridge Bird Observatory in Duluth Minnesota broke their previous one-day count for bald eagles with a whopping 1,076!

Bald eagles have composed 90% of the raptor migration count at Hawk Ridge over the last month.

But if the Hanover eagles are nearly a month into incubation, how is it possible that other bald eagles can afford to be so far behind? The answer exists in the diversity of migration patterns that exist across bald eagle populations, influenced strongly by the availability of their primary food source: fish. This in turn means that movement strategies are correlated with the location of nesting grounds.

The eagles being counted at Hawk Ridge are an example of this. The breeding age adults being counted at Hawk Ridge right now are coinciding their chick-rearing with plenty of open water. Just as many songbirds must time their return migrations with insect hatches to ensure their chicks will have plenty to eat, bald eagles must wait to return north until ice has a chance to melt so that fish will be plentiful, hence their later migratory movements and breeding patterns compared to birds here in Pennsylvania. If a pair of eagles tried nesting in Canada during winter months, fish would be sealed below ice, therefore preventing them from finding enough food to feed their hungry chicks. The eagles know this, and they adjust their movements accordingly.

Here in the Mid-Atlantic we see several movement patterns for bald eagles. Some, like Liberty and Freedom, stick around for most if not all of the winter or engage in short-distance movements south depending on resource availability. In June and July we receive an influx of bald eagles from Florida and Georgia which exhibit a true exception to most migratory patterns in North America. Floridan bald eagles are the only Northern Hemisphere raptor that travels North on “outbound” migration and South on “inbound” migration. They do so because in Florida, they have to contend with water that gets so warm in the summertime that fish seek cooler, deeper waters and while this vertical shift may only be a meter or so, it’s enough to put fish out of the bald eagle’s reach. After all, even though eagles are ambitious and will often row themselves to shore rather than give up a fish, they are not diving birds. Bald eagles that nest in Florida travel north during the summer to hunt fish closer to the surface and return to Florida in the winter to breed when fish there are easier to access. In September, Hawk Mountain records some of these individuals during their return migration South.

Swimming to shore. Photo: Daven Hafey.

Another example of carefully-timed eagle movements occurs in the Pacific Northwest. Those individuals are well attuned to the fluctuations of salmon spawning, and many migrate north to southeastern Alaska to meet salmon at the end of their journey.

Salmon at the end of their journey, Pack Creek, Alaska. Photo: Daven Hafey.

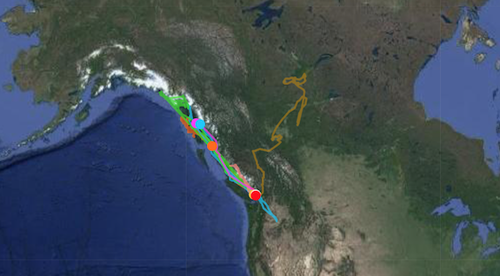

You may be wondering how anyone can possibly know where exactly an individual eagle is traveling to and from, since, for research purposes there is no natural way to guarantee you are seeing the same bird in two places. The answer is satellite transmitters. Researchers deploy devices that are light enough so as not to compromise the bird’s ability to fly, and through the cellular network or our satellite system, detailed information about a bald eagle’s whereabouts can be directly sent to a researcher. Through this technological development we have been able to obtain tracks illustrating the intentionally timed flights of these regal raptors.

Transmitter used for tracking. Photo: Myles Lamont.

Examples of tracks from tagged bald eagles, courtesy of Hancock Wildlife Foundation: https://hancockwildlife.org/project/beta-bald-eagle-tracking-alliance/

How incredible to think that while we watch Liberty and Freedom move into their home stretch of incubation, there are thousands of eagles that haven’t even begun. The range of movement patterns that exist within this one species is a true confirmation that no two bald eagle populations are alike, and furthermore, these noble fish specialists have an impressive tool belt with which to adjust their movements to ensure survival.

Liberty and Freedom’s first-laid egg is expected to hatch sometime towards the end of next week, though just as our own due dates are subject to change, keep an eye out because the 35-day average is just that – an average. We could see a hatchling on either end of April Fool’s Day!

SPECIAL NOTE:

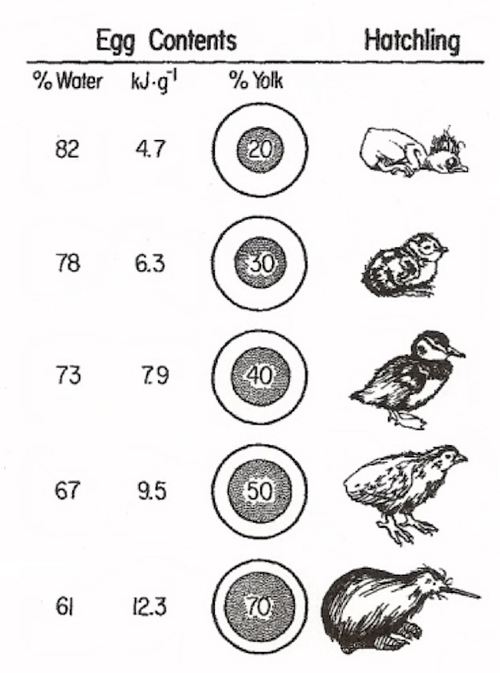

This chart shows how the % of water within a developing egg decreases throughout the incubation period as the developing yolk takes up more and more space. Species from top to bottom: Brown Creeper, Least Tern, Ruddy Duck, Mallee Fowl, and a Brown Kiwi. Notice the difference between the altricial (less developed) Brown Creeper and the other precocial hatchlings. The less developed the embryo at time of hatch, the smaller the yolk!

QUIZ QUESTION:

Are bald eagles altricial or precocial?

RETURN TO HANOVER BALD EAGLE BLOGS

WATCH THE HANOVER BALD EAGLE LIVE CAMS

For over 20 years, HDOnTap has provided live streaming solutions to resorts, amusement parks, wildlife refuges and more. In addition to maintaining a network of over 400 live webcams, HDOnTap specializes in design and installation of remote, off-grid and otherwise challenging live streaming solutions. Contact press@hdontap.com for all media needs, including images and recordings.